THE PERFECT BLEND: Erotic Capital, Playmates and the Vietnam War

- Stephanie Zundel

- May 10, 2022

- 9 min read

Updated: Aug 25, 2022

(Still, Charlotte Evans, "Blend" by Aldous Harding, 2017)

"Hey Man"

Aldous Harding starts to sing softly, her eyes fixed on us. The video starts with a close-up of her made-up face, complete with lashes, pinkish eyeshadow, coloured lips, perfect soft shiny skin, rouge and highlighter.

Blend, directed and edited by Charlotte Evans and produced by Evie Mackay was published in 2017. It is the opening track of the New Zealand singer's second album Party (2017). With its two-and-a-half minutes playing time it is a short song and video, and a masterpiece in its effect.

The setting is a clinically white room, brightly illuminated. Harding performs her song, for the camera, for us? The repeated eye contact makes the consciousness of an audience apparent. As she is singing the first verse, the camera steps back, her outfit and body are revealed. She is wearing a light blue top or bustier, sprinkled with shiny silver stars, held together with strings in front of her chest. This is matched with shorts of the same colour and ornament. Over the shorts, a white leather pistol holster with silver metal adornments completes the look together with brown heeled white cowboy boots.

Eerie bodily manoeuvres start – Harding turns away from the camera, which now shows her fully, with her knees touching and slightly bent, she wiggles her behind in a dance step, while making her silhouette small, her head slightly bent to the left and down. She turns back around, finds a wide stance, extends her arms and hands upwards to form an X with her body, still swaying. The dance continues after this full body introduction with close-ups of her hips, torso, bum, shoulders, altering with full body shots, again and again interrupted with Harding's glances at the camera. It is a focused, controlled way of moving – the dance, a choreography which would be deemed sexy, constructed to appeal, to become.

The effect, however, is tension and irritation – watching the video is not a comfortable experience. It presents strong contrast. Between the softness and calm of the song, which in its intensity remains stable, where Harding's layered vocals almost blend with the mellow guitar and the scarce percussion, and the bright light, colours and sterility of the scene. More impactful is the contrast between the signals of the choreography and the way that it is performed – movements and camera angles which typically invite to sexualize and objectify, make just that almost impossible.

Our gazing at Harding keeps on getting interrupted by her gazing at us.

Her looks are intense, puzzling and provocative. Loaded. How do you look at me? Can you withstand my gaze?

(Still, Charlotte Evans, "Blend" by Aldous Harding, 2017)

"I really need you back again"

Harding's focus and her controlled, at times strained facial expressions reveal that this is work. This presentation of self, the movements are work. Aldous Harding is working her body, crafting and calculating her signals.

We live in a society. In Europe and the US it is capitalistic and patriarchal, women and their bodies are still being harshly policed, judged and controlled. The international regressions in abortion policies are painful reminders and alert of a shift towards conservative and backwards views. In 2011 Laurie Penny discussed "Female Flesh under Capitalism" in her book Meat Market – in capitalism not only our work, our time, become commodities, so do our bodies. The dictum is: sex sells. According to Penny, a big part of being socialized into and learning femininity, a female gender role entails "the creation and maintenance of erotic capital". (Penny 11) This is far removed from an open discovery of one's sexuality and desires. What is in demand is "deodorized sexual transaction" (5), an "illusion of sex, an airbrushed vision of enforced fun-fisting sexuality that is as sterile as it is relentless" (8). It has little to do with real sex and sexuality, which can be messy, out of control and challenging to social categories and of course gender norms – this kind of sex is still subject to censorship and shaming, even if progress and open education are happening.

Understanding and acquiring the mastery of this sexual signing is a (female) task and duty:

"What many of us understand quite profoundly is that sexual performance and self-objectification are forms of work: duties that must be undertaken and perfected if we are to advance ourselves." (Penny 11)

Harding makes this work visible in her performative and interruptive self-objectification.

(Still, Charlotte Evans, "Blend" by Aldous Harding, 2017)

"Can't seem to let you off the chain"

The lyrics tell a story of attachment and struggling to let to, while Harding dances her jerky 'sexy dance'. The colour palette of the video is blue, red/pink and white. Together with the stars, the cowboy boots and the 'shooting' of the pistols this rings 'USA'. A quick internet search reveals to those who did not know already that the video is a clear reference. Harding is cited stating:

"The concept is based on that awful scene from 'Apocalypse Now' where the Playmates pile out of the helicopter. The costume was handmade for me, it turned out great. It's in the bin. I spent eight hours dancing on a Lazy Susan, it was easy really. Obviously, I know what it is… The song itself was written in an AirBnB in Bristol the night before going into the studio."(Fuamoli)

That awful scene from Francis Ford Coppola's 1979 movie Apocalypse Now depicts an attempt to acknowledge the American soldiers' hardships by awarding them with some "special entertainment" – three Playmates emerge out of a helicopter and dance for a crowd of screaming, applauding soldiers. The 'main attraction' is Carrie Foster, the Playmate of the year, played by Cynthia Wood, actual Playmate of the year 1974. Harding's outfit is an exact replica of Wood's, except for the white cowboy hat that is missing. Harding's movements are also almost exact repetitions, from the opening bum-wiggle and X-pose, to the wiping of the nose with the back of the hand, the forward extended intertwined arms and hands while bending the knees, the playful shooting and then pointing the pistols towards the groin area.

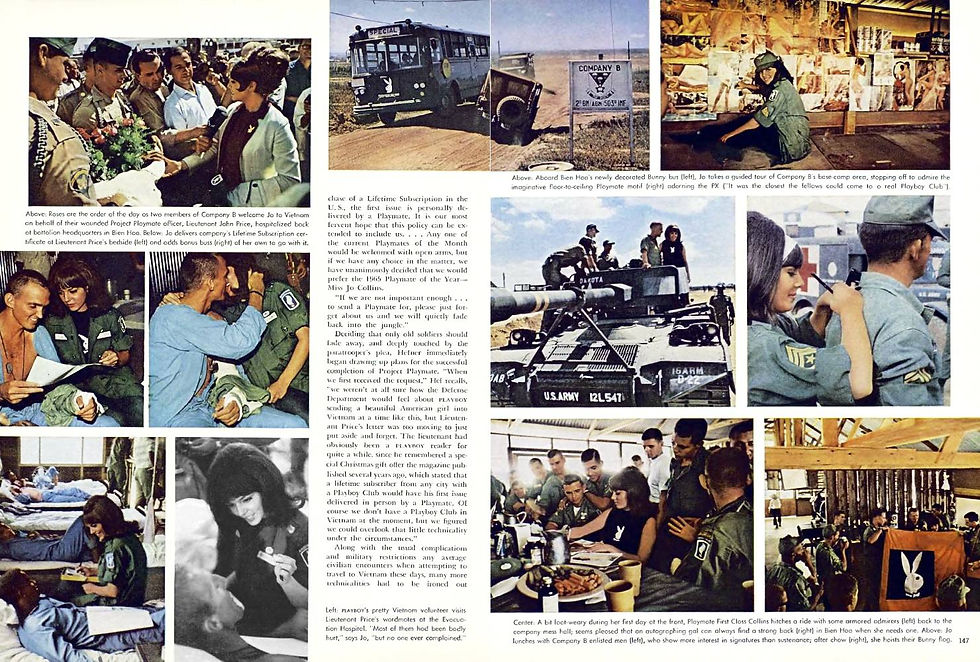

A event like this never actually happened during the Vietnam War, even if Jo Collins, Playmate of the year 1965, did personally deliver a lifetime Playboy subscription (as was part of the deal at the time) to Jack Price and the 173rd Airborne Brigade all the way to the hospital in Biên Hòa where these men were stationed and met them and many more soldiers. (Palopoli)

(Scan, a double page from the article "Playmate First Class: Jo Collins in Vietnam" from the May 1966 edition of the Playboy)

In fact, the Playboy magazine was profoundly influential for and even directed at American soldiers during the Vietnam War: "[A]s entertainment, yes, but more important[ly] as news and, through its extensive letters section, as a sounding board and confessional. […] [T]he publication became a coveted and useful morale booster, at times rivaling even the longed-for letter from home. Playboy branded the war because of its unique combination of women, gadgets, and social and political commentary, making it a surprising legacy of [American] involvement in Vietnam." (Batura)

This seems surprising and possibly absurd at first. Yet the visiting of beautiful women, pin-ups in the Second World War, at the front in the name of patriotism and nationalism is a known phenomenon. Eventually, it blends perfectly into reflections about the instrumentalization of women for propaganda and nationalism (e.g. the perfect Aryan woman in the Second World War), homosocial spaces, performative masculinity and sexuality.

The Playmates from the magazine were stylized as "real women their readers might see in their everyday life – a classmate, secretary or neighbor – instead of the highly stylized and often famous women of an older generation. The sexualized, yet familiar, 'girl next door' was the perfect accompaniment for soldiers stationed in Vietnam. This conception of wholesome, all-American beauty and sexuality acted out by largely unknown models reminded young soldiers of the women they left behind, and for whom they were fighting – and could, if they survived, imagine returning to." (Batura) The conceptualization of this movie scene is therefore anything but far-fetched.

The ecstatic soldiers in the improvised amphitheater collectively perform their desire and need for (these) women, they scream: "Take it off!", "Grease my gun!", "You fucking bitch!" – the verbal transgressions are soon followed by physical ones, as the stage is stormed and the performers have to be evacuated.

Actress Colleen Camp remembers the filming experience: "It's martial law; there's 400 men and three women. […] When the G.I.s started to rush the stage, it was actually scary. It was very quick – the girls get scared, they have to get back into the helicopter, and they're hurried off the stage. But it was actually planned out really well, so we weren't in any danger – except that, you know, helicopters are extremely dangerous." Chyntia Wood did not recall being warned about the storming of the stage previously. (Palopoli)

(Photograph, Cynthia Wood as Miss May in Apocalypse Now, 1979)

Like the music video this scene is uneasy to watch, the danger and tension are palpable, it is absurd, disturbing. What is the point?

Francis Ford Coppola explains: "The point I was trying to make was that in a way the abuse of sending a 17-year-old boy to Vietnam to drop napalm on people is as immoral as what is done to these young, beautiful girls at 17. That was a symbol of abuse – what we do to the young men, we also do to the young girls in our so-called civilization." (Palopoli)

The show represents a (sexual) transaction: Soldiers are supposedly compensated for investing their whole sustenance in this war, the young women's sexual appeal is offered as said compensation. Different kinds of human capitals are offset here, the physical, mental, emotional, erotic. The result is a scene that exposes the horror and the inhumane in just that commodification of human beings, human bodies by the state and the patriarchy, the patriarchal state, that abuse which Coppola addresses.

This perspective is not meant deny the involved people their humanity and agency, but to reveal the parameters which shape this interaction and underlie the construction of the scene.

The transaction is obviously not successful. All parties leave the scene unsatisfied and exploited.

"You're the perfect blend"

Towards the end of the song Harding's movements get a little faster, a little more choppy. Increasingly alienated from her facial expressions which make the dissonance so apparent. She is performing that this is a performance.

The lyrics land on: "And you're the perfect man, You're the perfect man, You're the perfect blend" and in the outro a ringing sound introduces dissonance into the audio dimension, too. This 'you' that is addressed, who cannot be let off the chain, who is so hard to let go, is perfect. A perfect man. A perfect man. The perfect blend.

Is Harding working her dance, dancing her work for him? Why does she slip into the role of a Playmate?

"The Playmate, originally introduced as the Sweetheart of the Month, represented the ultimate companion to the Playboy. She enjoyed art, politics and music. She was sophisticated, fun and intelligent. Even more important, this ideal woman enjoyed sex as much as the ideal man described in the publication. She wasn't after men for marriage, but for mutual pleasure and companionship." (Batura)

The Playmate is 'the ideal woman'. 'Ideal' as in non-demanding, smooth, agreeable. No edges, no darkness. Herself the perfect blend of femininity, with little to no expectations but everything pleasurable to give. Laurie Penny quotes Hugh Hefner: "Consider the kind of girl that we made popular: the Playmate of the Month. She is joyful, joking, never sophisticated… We are not interested in the mysterious, difficult woman." (15)

For this song of longing, missing, remembering Harding becomes the Playmate of the year, the most desired woman, an easy woman. However, her portrayal is flawed, and twisted so that the illusion of the 'perfect woman' is exposed. On the level of lyrics, too: The second line already expresses want, need, demand: "I really need you back again". Harding is demanding, in how she addresses the 'you', in her challenging performance, in her gaze.

Why miss someone for whom you have to work so hard and paint over your true colours with glossy shine?

This question seems a shortcut. Might Harding's portrayal and dismantling of the illusion imply that this 'perfect man' himself is not the perfect blend either?

Directed and edited by Charlotte Evans & Produced by Evie Mackay.

(Re-)Sources

"Apocalypse Now Playboy bunnies scene Playmates HD". youtube.com: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-oEKQTc-4O8&t=1s

Batura, Amber. New York Times. "How Playboy Explains Vietnam": https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/28/opinion/how-playboy-explains-vietnam.html

"Blend". youtube.com: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-oEKQTc-4O8

"Blend Lyrics". genius.com: https://genius.com/Aldous-harding-blend-lyrics

Davis, Susan E; DeMello, Margo. Stories Rabbits Tell: A Natural and Cultural History of a Misunderstood Creature. New York: Lantern Books, 2003.

Fuamoli, Sosefine. "Music Video of the Day: Aldous Harding 'Blend' (2017)": https://www.theaureview.com/music/music-video-of-the-day-aldous-harding-blend-2017/

Linehan, Adam. "Hugh Hefner's Playboy Was The Magazine Of The Vietnam War": https://taskandpurpose.com/history/hugh-hefners-playboy-magazine-vietnam-war/

Palopoli, Steve. playboy.com. "The True Story of the 'Apocalypse Now' Playmate Scene": https://www.playboy.com/read/apocalypse-then

Penny, Laurie. Meat Market. Hants: Zero Books, 2011.

Perry, Kevin EG. The Guardian. "Francis Ford Coppola: 'Apocalypse Now is not an anti-war film'": https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/aug/09/francis-ford-coppola-apocalypse-now-is-not-an-anti-war-film

Rogers, Jude. The Guardian. "The strange world of Aldous Harding: 'I've always been driven by fear'": https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/nov/17/strange-world-of-aldous-harding-driven-by-fear-interview

Wolf, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty are Used Against Women. New York: William Morrow & Co, 1991.

Wakeman, R. "Playmate First Class: Jo Collins In Vietnam, May 1966":

Comments